|

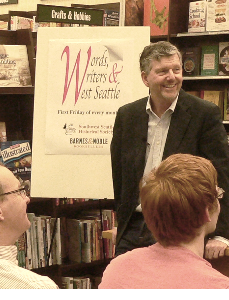

Conrad appeared as the featured author at "Words, Writers & West Seattle" on March 7, 2014 -- an event hosted by Barnes & Noble, booksellers and the Southwest Seattle Historical Society. Link to YouTube video below. Conrad appeared as the featured author at "Words, Writers & West Seattle" on March 7, 2014 -- an event hosted by Barnes & Noble, booksellers and the Southwest Seattle Historical Society. Link to YouTube video below.

|

|

ON WRITING...

Structure

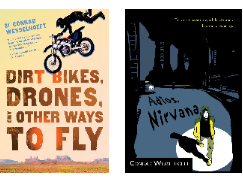

The nice thing about the structure of a novel--as opposed to the structure of, say, a cathedral--is that the revision process lets you go back and add bolts and girders, without everything imploding. Even when I'm deep into the revision process, I can add one little bolt (a sentence in chapter seventeen of Dirt Bikes, Drones and Other Ways to Fly, for example) that strengthens the entire book. That one change can add texture, meaning, and illumination to everything else. And yet I'm often unaware of the need for that bolt until late in the creative process.

Marketing your stories

The best marketing strategy is to write a good story. That's where an author's primary focus should be. If you succeed at that, then blogging and schmoozing and web sites should come easily. Hunker down and spend ninety percent of your time and energy on writing, and ten percent on marketing. On second thought, spend ninety-FIVE percent of your time and energy on writing. All the marketing in the world will not turn a weak story into a strong one. Conversely, a strong story will probably harmonize with any marketing strategy. My own agent and editor seem far more interested in the work itself than in marketing.

So far, I have spent ninety-nine percent of my time on writing, one percent on marketing. That's probably too extreme.

Self doubt

Years ago, I was filled with darkness and doubt about my writing. I seemed to be going nowhere and never getting published. I complained to my writing friends, who said, be patient, that behind the darkness and doubt, something good was brewing. Of course, I doubted them. But they were right. Self-doubt is natural in a writer and may even be a necessary and important part of the writer’s journey, pushing one to new heights. The key is, persevere. Never give up.

Storytelling

-

Good fiction is good storytelling. If awesome metaphors and scintillating dialogue don’t serve the story, they don’t belong. Storytelling is the key. This is no different than what our ancestors were doing around the smoky fire, telling stories.

-

If a novel were a card deck, then the story would be the ace high. Metaphor, dialogue, hyperbole, setting, and other characterization tools would be of lower value. Too often, however, we let these lower cards trump the ace. For example, writers frequently use exclamation points, italics, or all caps for emphasis. But instead of emphasizing a point, they tend to shout at the reader, thus distracting from the story. "An exclamation point is like laughing at your own joke,” said F. Scott Fitzgerald. I think it’s important to turn down your volume and let the reader supply the emphasis. A quietly written story can ring loud in a reader’s ear. I also like what Eudora Welty had to say about beautiful phrases that get in the way of the story: "Kill your darlings."

I believe that stories pull us closer together, as small groups and larger societies. Storytelling is more than mere entertainment; it is essential--for teller and hearer alike.

Finding your rhythm

Some of your best writing happens when you are farthest from your tools. Often, my best ideas come to me while I'm walking my dog. He tugs on the leash, barks at other dogs, growls at cats, sniffs the shrubs. We take the path down to the beach. On a lucky day, we spot an eagle or sea lion. In some ways, this is the most productive part of my writing day--the time when my best ideas reveal themselves. A rote activity--one that has an easy physical rhythm to it (walking, running, raking leaves, doing dishes)—can grease the wheels of the imagination far more efficiently than sitting at your desk.

"A Writer's Journey: Author Conrad Wesselhoeft talks about the source of his inspiration for creative writing."

Hope

As a writer, I choose themes that are important to me. Foremost are hope, healing, family, and friendship. These are themes I’d like my own children to embrace. Life can be hard and seem hopeless, so as a writer I choose to send out that “ripple of hope” on the chance it may be heard or felt, and so make a difference.

In Praise of Place: Why fiction writers should light out for personal territory

In my mid-twenties, I fell in love with northeast New Mexico—the high plains, broken mesas, torn shadows, and rich, drifting light. I lived for two years in the town of Raton, working as a journalist for the local newspaper.

Working for a small-town paper meant doing every job in the newsroom: writing and editing stories; laying out the paper on a composing table; and taking and developing pictures.

I took thousands of photos, criss-crossing the county with my sturdy Pentax K1000 camera—later moving on to a more nimble Canon AE-1.

The vistas of northeast New Mexico enthralled me. Much of the time, they looked flat and dull, but at certain times of day, under certain light, they exploded with beauty.

I’d reach for my camera, and all would go quiet.

Several years ago, when I started writing my young-adult novel Dirt Bikes, Drones, and Other Ways to Fly I wanted to re-capture that special landscape—both the look and feel of it.

I started by creating a fictional town and calling it Clay Allison, after the 19th Century gunfighter who had lived in that area. I jotted these notes:

“Clay Allison is a town in northeast New Mexico located in the high desert snug up against Colorado’s mountainous ass. ‘Clay’ has a rusty, shoddy, past-its-prime look and feel. In reality, it has never experienced a prime.”

The surrounding landscape, I noted, “is a hundred muted shades. Nearby are Eagle Tail and Burro mesas, and to the north, the Sangre de Cristo (Blood of Christ) Mountains. Many small mesas are carved with dirt-bike tracks, an insult to Mother Nature, but a playground for Arlo Santiago and his friends.”

Arlo is the novel’s 17-year-old adrenaline-junkie narrator. He loves to blast across the mesas on his Yamaha 250 dirt bike, hitting the bumps and flying high.

I stretched my vocabulary when I wrote:

“The story unfolds under the cerulean emptiness of New Mexico’s slow-fuse sky.”

My goal was to have Arlo fit organically into this landscape. I wanted him to respond—consciously and otherwise—to the monotonous-one-minute, staggering-the-next horizons, just as I had. If he could do this, then maybe readers could, too. That was my hope anyway.

Whether I pulled it off is not for me to say. What I did learn, however, is how important setting can be to a story—so important, in fact, that it can become a galvanizing character in its own right, one filled with moods and fancies, passions and mysteries.

Writers often overlook setting in favor of other vital characterization tools—like plot or dialogue.

The result is that New York City appears no different in the mind’s eye than Portland, Oregon, and the Grand Canyon exudes all the gravitas of a touched-up postcard. Hasty writers repeatedly locate Denver in the Rocky Mountains when, in fact, “the Queen City of the Plains” is located just east of the Rockies.

It’s as if the writer had stuck a pin on a map and said, “I think I’ll set my story here.”

But when setting works—when a writer taps into emotions associated with a place—it can be glorious, as in Huckleberry Finn (the Mississippi River), The Old Man and the Sea (the Caribbean), or To Kill a Mockingbird (small-town Alabama).

It’s no coincidence that Twain, Hemingway, and Harper Lee lived and worked where they set their stories, or that they acquired far more than an eyeful of land or water. By the time they embarked on writing their novels, they had mingled their souls with those places.

And therein lies the beauty of “place” or “setting” in fiction.

When a writer dips into his or her own life and bares emotions connected with a place the result can transform and exalt a story.

Scott O’Dell’s love for California’s coastal islands shimmers on every page of Island of the Blue Dolphins, his 1960 young-adult novel about a girl left on a remote island to fend for herself. You more than hear the gulls cry, waves crash, and wind blow. The island on which Karana lives seems alive. You hear it mourn for all that is missing from her life, just as it rejoices in her victories over storms, hunger, and wild dogs.

Lois Lowry drew on memories of growing up on military bases to create the stark, regimented world of her 1993 dystopian novel The Giver.

C.S. Lewis based his sweeping Narnia vistas on the Mountains of Mourne in Northern Ireland. About them, he wrote: "I have seen landscapes . . . which, under a particular light, make me feel that at any moment a giant might raise his head over the next ridge.”

In every case the writer traversed a personal geography to inform a fictional one. His or her emotional connection to a real place grounded the reader in an imagined setting.

Contemporary young-adult fiction writers traversing this personal geography include Molly Blaisdell, whose Plumb Crazy makes small-town Texas taste like a sweet-potato pie glazed with dust and peppered with grit; Louise Spiegler, whose historical novels capture the damp majesty of Puget Sound country; and Holly Cupala, whose Don’t Breathe a Word gives the midnight alleys of homeless America a heartbeat.

When a writer soaks up the spirit of a place—whether it’s a town, city, mesa, or just about anywhere else—that place can inspire a profound fictional setting.

A great story puts you there, so that you see and feel the landscape around you. Writers get there by digging into their personal geography—and listening for the heartbeat.

|

|

A Writer's Journey:

Author Conrad Wesselhoeft talks about the source of his inspiration for creative writing.

During Conrad's career as a journalist, he was assigned to interview author Scott O'Dell (Island of the Blue Dolphins). Click here to learn how this pivotal experience helped to kick-start Conrad's career as a writer.

A Note to Conrad from Mrs Scott O'Dell:

Hi Conrad,

I’m delighted to hear that you’ve published your second YA novel. Scott would have been so pleased, not only because of your success but because you actually followed his advice and got right down to writing. I still have a copy of your interview with Scott from the NYTimes. Next month marks the 25th anniversary of Scott’s death, but his books—especially Dolphins—are still going strong and new editions are still appearing around the world. All my wishes for your continuing literary success.

Mrs. Scott O’Dell

DIRT BIKES, DRONES, AND OTHER WAYS TO FLY is a 2014 Junior Library Guild selection.

DIRT BIKES, DRONES, AND OTHER WAYS TO FLY landed on Air & Space/Smithsonian’s 2014 list of Best Aviation and Space-Themed Books for Young Readers. The list is an annual roundup of children’s and YA titles that focus on flying.

|

|

Conrad appeared as the featured author at "Words, Writers & West Seattle" on March 7, 2014 -- an event hosted by Barnes & Noble, booksellers and the Southwest Seattle Historical Society. Link to YouTube video below.

Conrad appeared as the featured author at "Words, Writers & West Seattle" on March 7, 2014 -- an event hosted by Barnes & Noble, booksellers and the Southwest Seattle Historical Society. Link to YouTube video below.